It’s more than musical ecstasy: Constructing the field of electronic dance music culture in Georgia

Image Credit: Matthias London.

I chose the set because KI/KI played on my birthday in Bassiani in 2020.

It’s more than musical ecstasy: Constructing the field of electronic dance music culture in Georgia

I got waves of intense feelings I have never felt before. I got intrigued and fascinated. I felt welcomed. I felt at home. I felt like I was where I was. I felt like I was where I was supposed to be. And I wanted to be there. And in the midst of all this chaos and stomping, euphoria and happiness, beautiful shapes and shadows, blinding lights up, screaming and laughing, I saw a certain type of harmony; like, there was a certain type of harmony in this chaos. I don’t know if that makes sense, but it makes sense for me. And like I felt like I finally found that special something – that true and pure excitement – I was seeking for so long. And I felt like I found a community I was looking for. And I left emptied and at the same time filled with emotions that day. I left so much there, but I also took so much there at the same.

– Diana, agent in the field of EDMC in Tbilisi, Georgia

1. Introduction

For many, the exposure to electronic dance music culture (EDMC) catalyzed a process of identity construction that empowers alternative lifestyles beyond the shelter of the night. That also holds true for Caucasian Georgia, a post-communist country with a profoundly Christian Orthodox population in transition to neoliberal capitalism. Georgia’s recent transformation sideling the surge of globalized capitalism instigated political, economic, and cultural reforms that affected different age groups dissimilarly. Therefore, it caused substantial cleavages between the post-communist youth and the older pre-capitalist generation. Despite the crystallization of neoliberal national identity, the post-communist generation’s most intimate milieus of life – such as family and friends – keep inscribed with Christian Orthodox values and the heir of a communist political economy. Consequently, the process of solidifying lifestyles that alternate from societal norms perpetuating pre-capitalist social structures plays out as an intergenerational struggle in the arenas of culture, ideology, and politics.

As an entry point to unearthing the complex dynamics at play, I humbly attempt to construct the Georgian field of EDMC informed by Bourdieu’s sociology of culture in this paper. For this purpose, it starts with a brief overview of Bourdieu’s most relevant theoretical concepts for field construction, i.e. capital, habitus, field, and their relation within the overall social space. The subsequent participant observation substantiates my theoretical assumptions, namely that the analysis of the Georgian EDMC field requires the consideration of global field dynamics, that competition is secondary in the Georgian EDMC field, and that agents who navigate it embody a plurality of habitus. To confront these assumptions with empirical data, I conducted five qualitative life-course interviews with members of the Georgian dance community and interpreted them employing Bohnsack’s documentary method.

First, the study’s results suggest that in imitating established club concepts and trending musical styles, the Georgian EDMC field maintains a vertical relation to the overarching global EDMC field while adapting the unilateral stimuli to the local particularities of the scene. Second, although cultural producers are strategically led by an internal aesthetic drive that fuels the struggle for recognition, I found that the field of EDMC consumption is less internally competitive than generally assumed by Bourdieu. The externally imposed misrecognition from the field of power mitigates the internal struggle by consolidating a social group that vigorously intends to overcome internalized structures of domination. I deduced from my interlocutor’s habitus that agents in the EDMC field embody a traditional primary habitus which they intend to deconstruct entirely in replacement for liberal secondary one. In spite of the EDMC agents’ conscious effort to reduce this habitus duality to a singular, liberal one, it is likely that they mutually influence each other in the production of distinguishable actions within the specific social environment in which the agents find themselves. Lastly, in recognition of the various limitations, I conclude this paper with implications for future research that would do justice to the complex interplay between global-local positions and the region’s history in the making of the Georgian EDMC field’s struggle for legitimacy.

2. Theoretical framework: Bourdieu’s field theory

Bourdieu did not offer strict definitions and one-size-fits-all application methods, as his research program invites scholars to translate his theoretical concepts into actual research practice while adapting them to the contextual particularities. His reflexive sociology offers a multitude of concepts that relate to each other in the construction and study of the research object within the overall social space. It is not my intention to wholly depict Bourdieu’s theory of practice, therefore, in this section, I will briefly elaborate on the concepts relevant for the construction of the EDMC field in Georgia and their relationship to one another, i.e. field, capital, and habitus.

In abstract terms, Bourdieu (1989: 15 – 16) argued that we can understand social reality as a web of relations that establishes an objective social space through the relative distance of mutually external positions vis-à-vis one another. More concretely, he stressed that in differentiated capitalist societies it is necessary to construct a multidimensional space – conventionally at its largest equated with the nation-state of the society under investigation (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 111 – 112) – consisting of a plurality of relatively autonomous fields that agents navigate while competing over valued resources (capitals). Following the axiom of relationality undergirding his sociology, Bourdieu (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992: 96) asserted that notions such as field, capital, and habitus are intrinsically linked and cannot be defined in isolation. Thus, Bourdieu (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992: 97, original emphasis) defined a field as

‘a network, or a configuration, of objective relations between positions. These positions are objectively defined, in their existence and in the determinations they impose upon their occupants, agents or institutions, by their present and potential situation (situs) in the structure of the distribution of species of power (or capital) whose possession commands access to the specific profits that are at stake in the field, as well as by their objective relation to other positions (domination, subordination, homology, etc.).’

It follows that to construct a field, researchers need to elucidate what the struggle in the field is about. As indicated by the above definition, Bourdieu used fields as spatial metaphors that become the sites in which agents play out the competition for control over the forms of capital valued in the field under study – or in Bourdieu’s (1989: 21) words, the struggle for the ‘monopoly over legitimate symbolic violence’. Bourdieu (1989: 17, 2000 [1984]: 250, 2006 [1992]: 10; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 98) often metaphorizes fields as ‘games.’ In these games, capitals are resources that are necessary for their holders to access socially valued activities and positions that enable them to yield power. Bourdieu (1987: 17, 1989: 3 – 4) identified economic, cultural, social, and symbolic capital as the fundamental types of capital that are prevalent across fields. He subsumed different types of resources under each notion of capital, for instance, education, artistic skills, or cultural objects as resources relevant in the cultural realm, income and wealth as indicators for economic capital, and membership in exclusive clubs or acquaintance with powerful people as social capital (Bourdieu, 1987: 4). Because a ‘capital does not exist and function except in relation to a field’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 101, emphasis removed), capitals and their components tend to proliferate sidelining the proliferation of the fields into ever more concrete sub-fields. Consequently, a capital’s occurrence and degree of value differ within each respective field. When a field’s holder of symbolic power recognizes some kinds of capital as legitimate in the field, they transform into symbolic capital. Therefore, the struggle over capital is a struggle over symbolic classifications and definitions regarding what counts as a capital as well as a strategical struggle over the dissemination of those forms of capital.

Since fields are structured according to the (unequal) distribution of the types of capital active in it, researchers who intend to construct a field need to elucidate the different kinds of capital valued in it. Social positions occupied by agents are predominantly determined by the overall volume of capital held by them in the first dimension, the relative weight each type of capital constitutes in the total volume in the second one, and the development of volume and structure of their capital over time in the third dimension (Bourdieu, 1987: 4, 2000 [1984]: 114; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 99). An array of agents thus constitutes a web of field positions that are related in their spatial proximity or distance. Especially the demonstration of positions according to diverse amounts of cultural and economic capital held by agents illustrates a system of opposing standpoints. The spatial distances between the various antagonistic positions within the same social field produce its structure in that they demark the field’s horizontal poles as well as its hierarchical establishment (Bourdieu, 2000 [1984]: 120) and therefore also its boundaries (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 98 – 99).

The construction of a field structure goes hand in hand with the identification of the important players in the field who are occupying the relative positions producing this structure because their competing behavior unearths field dynamics. Agents can be, for instance, individuals or groups such as institutions or organizations that are imprinted with empirical data necessary for field analysis. However, Bourdieu (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 107 – 109) emphasized that they only matter insofar, as they are conceptualized as social agents – not as biological subjects –, i.e. as bearers of a specific mix of capitals and social trajectories that determine their stance toward the game. The oppositional viewpoints by agents within the hierarchical structure of the field unravel dominant, subordinate, and intermediate positions that are laden with different strategic orientations toward the struggle for symbolic authority. This implies that the agents understand and accept the field-specific rules of the game – which Bourdieu (2008 [1980]: 66) names ‘doxa’ – and are invested in it –which he frames ‘illusio.’ Agents holding dominant positions will likely tend to follow an ‘orthodox’ (Bourdieu, 2006 [1992]: 205) strategy that maintains the prevalent social hierarchy, meaning preserving the configuration of capitals that places them in a dominant position. On the contrary, agents occupying a subordinate position are likely to follow a strategy of ‘heresy’ (Bourdieu, 2006 [1992]: 205) that aims at transforming the capital configuration (read: field structure) by accumulating more capital or implementing new kinds.

Field analysis further requires the clustering of the involved agents that are differentiated by their (class) habitus. Bourdieu (2008 [1980]: 50) perceived social practice against the background of the relationship between social class habitus and current capital as mediated by the specific logic of a given field. The relative proximity of various positions within a field allows for social classification, as similar amounts of capital volume, structure, and social trajectories indicate a history of similar conditions of existence experienced by the agents occupying the positions (Bourdieu, 1987: 5). Subsequently, Bourdieu (2000 [1984]: 110, 2006 [1992]: 85, 2008 [1980]: 53) argued that there is a strong correlation between an agent’s social position and their habitus, i.e. their internalized set of dispositions resulting from class-based conditions of primary socialization that produce distinguishable schemes of actions, perceptions, and aspirations. Since social positions program agents to learn certain patterns of behavior which they reproduce in specific social environments, classes of agents who are placed starkly oppositional from each other within the social space are likely to embody a dissimilar habitus that catalyzes the production of discrete class-based lifestyles. Therefore, according to Bourdieu (2000 [1984]: 105), the analysis of social practices links back to the field structure intersecting with habitus (and thus capital configurations) in the production of these practices.

Lastly, as agents necessarily navigate multiple social fields in their everyday conduct and both their capital and habitus are (in parts) transferrable across fields, researchers need to posit the field under study in relation to other fields, specifically to the field of power. Bourdieu (2000 [1984]: 30, 2006 [1992]: 55; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 103) explains the interconnectedness of fields and their capacity for self-governance in assessing their ‘relative autonomy’ from other fields. For this purpose, Bourdieu (2006 [1992]: 216 – 221) distinguishes between external and internal readings of fields. The autonomy of a field is a function of the degree to which it is capable of self-determining its internal logic and rules of functioning, under the absence of external influences from the overarching fields in which it is embedded. That implies that any given field finds itself in hierarchical relations with other fields (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 104). Conventionally, Bourdieu (2000 [1984]: 3, 2006 [1992]: 340; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 109 – 110) exemplifies this with the struggle of the cultural field for autonomy from economic, political, and religious forces.

In summary, fields are open concepts that require construction against the concrete particularities of the context to which they are applied. They are spaces of objective relations between social positions that are determined by the unequal distribution of volume and mix of different kinds of capital. In combination with agents’ unique social trajectories, their position (read: volume and composition of capitals) in the field determines their strategic stance toward the struggle for authority under consideration of their dispositions (read: habitus). Consequently, field construction is relational in multiple ways: It requires the simultaneous uncovering of the field-relevant capitals and the habitus produced by them and it requires the positioning of the field under study in relation to other social fields.

3. A night out in Georgia’s capital Tbilisi

In this section, I will spell out my research assumptions based on participant observations conducted during my stays in Georgia as well as my individual experience as an agent in various EDMC fields around the globe. My main assumptions are that (a) I cannot construct the EDMC field in Georgia without considering the influence of a global EDMC field, (b) that agents navigating the field of EDMC consumption are required to act according to a plurality of habitus in their everyday life, and (c) that the field of EDMC consumption is not as competitive as generally assumed in Bourdieu’s field theory. Though, before getting there, I will start this section with a brief contextualization of Georgia’s recent history.

Georgia is a country in the Southern Caucasus with a standing history of complex geopolitical struggles and a post-Soviet past in transition to (neo)liberal democracy. This transformation had two critical moments manifested by two popular social movements and subsequent changes in governance: Independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 and the Rose Revolution in 2003 (Roberts et al., 2009). The disintegration from the Soviet Union brought about significant changes impacting the sociopolitical and economic landscape; primarily an independent national identity, the move from a one-party system to a multiparty rule with augmented political participation, and market-oriented reforms harboring the solidification of a neoliberal identity in politics and economics (Nikolayenko, 2007). However, the abrupt transformation from Soviet norms and values in the transition to something new remains in progress and presumably builds on exactly these pre-capitalist social structures that it seeks to overcome. This is exemplified by the struggle for symbolic power in which the Georgian Orthodox Church (GOH) continues to play a pivotal role (Mebagishvili et al., 2012).

Upon my arrival in September 2019, already the first taxi ride from Tbilisi’s airport to its downtown staged striking discrepancies between different parts of Georgia’s capital. First, the periphery rooted massive housing blocks into its landscape that stamped the heir of Soviet developmentalism into the concrete. Shortly thereafter, a myriad of cultural hubs housing polychrome spaces and trendy people inhabiting them tinted parts of the city center in the paint of a ‘late modern’ (Giddens, 2003 [1991]) turn. One of these hubs was ‘Fabrika,’ a former Soviet sewing fabric that now functions as a meeting point for the progressive local youth and hostel for international travelers. I was barely able to register the overwhelming spectrum of shops offering cultural consumer commodities – such as music records, skateboarding gear, graffiti supply, designer clothes, cuisines from all around the globe, and barbers fusing with bars – before someone approached me with an invitation to the nightclub ‘Bassiani.’ It was Friday after all, they said, and that I arrived just in time for the season-opening – an invitation I was pleased to follow.

The similarity between what I found behind the doors of Bassiani and what I know from clubs in Berlin, like ‘Griessmühle’ or ‘Berghain,’ was tremendous. A long queue mouthing in a strict door policy as a first hurdle to enter is one of the things that granted Berghain its international legend status. Inside, my attempt to walk down a long dark path was interrupted by a hand that flipped into my sight, emerging from a bouncer who shook his head; okay, no entry for me here, this area must be exclusive. On my way to the dancefloor, I passed some darkrooms on my left-hand side. Everyone on the dancefloor faced the pedestalized DJ who played side by side two men voguing to high-energetic, industrial techno tunes. The crowd was rather homogenously stylized, wearing predominantly black clothing – often quite little – emphasized with BDSM accessories. Under these circumstances, the immediate reaction to sexual harassment was the intransigent eviction from the club. I observed a man putting down his empty drink, talking loudly to his bystander, followed by a move to his pocket to take out his phone for a video, which the surrounding clubbers immediately sanctioned by reproaching him for all of his acts – no photos allowed and no nuisance on the dancefloor. This environment seemed like it was directly imported from Berlin which gives reason to my assumption that the EDMC field in Georgia cannot be explained solely within the borders of the nation-state and instead requires the consideration of a vertical relation to an overarching global EDMC field.

It furthered seemed to me that the internal dynamics of the Georgian field of EDMC consumption are driven more by harmony than they are by competition. The genesis of the Georgian EDMC field was relatively recent – as most EDMC fields around the globe –, therefore, it is likely to have a low degree of relative autonomy from the fields of religion, politics, and economics, instigating a phase of external struggle for (artistic) legitimacy. Since agents navigating the EDMC field – on both production and consumption sides – are often stigmatized and bedeviled, it is my assumption that their strategic position-taking intends unity against external forces rather than internal competition for symbolic authority. Consequently, I assume that the field of EDMC consumption is more decentralized, less hierarchical, and less competitive than demonstrated by Bourdieu in his study on museum visits (Bourdieu et al., 1991) or judgment on taste (Bourdieu, 2000 [1984]). Qualifying this, I suggest that this holds true for the field of EDMC consumption, less so for the field of production, as spaces like Bassiani still function within the logic of Georgia’s reformed market economy and globalized capitalism.

Provided the recent transformation from a communist value system to a neoliberal one, I assume that most agents navigating the EDMC field developed a plurality of conflicting habitus for different social environments. As the above participant observation indicates, the nightlife club setting underlies a certain logic including (in)appropriate patterns of behavior. My observations of and interactions with such agents confirmed that this seems to partially hold true throughout their everyday conduct. The ‘liberal’ values and norms practiced by the post-communist participants in the EDMC field diverge blatantly from the pre-capitalist ‘traditional’ ones internalized by large portions of Georgian society. Principally, the socialization through traditional families is likely to incite a primary habitus in accordance with pre-capitalist ways of life that EDMC agents attempt to overcome in later life stages. Many of the agents navigating the EDMC field will need to guise their EDMC habitus in their everyday conduct to avoid social sanctions – for instance, when dealing with their family – and thus produce heterogenous habitus dynamics.

4. Methodology: Bourdieu’s cultural fields and Bohnsack’s documentary method

For the construction of the Georgian EDMC field, I differentiated between the field of cultural production and consumption and respectively employed different methodological approaches. I subsumed the production of electronic music under the cultural field of music and followed Bourdieu’s approach to exploring cultural production fields as outlined in The Rules of Art. The explication of this approach constitutes the first part of this section. Thereafter, I will explain Bohnsack’s (2010, 2014) documentary method, which I employed for the interpretation of five qualitative life-course interviews that I conducted with members of the EDMC scene.

As indicated earlier, field construction demands the simultaneous consideration of the three interrelated concepts habitus, capital, and field. Accordingly, in The Rules of Art, Bourdieu (2006 [1992]: 214) outlines general instructions for constructing fields of cultural production, such as the literary, poetic, scientific, artistic, or musical fields. For the construction of the Georgian EDMC field, I will follow his instructions consisting of three interlinked steps:

‘First, one must analyse the position of the literary (etc.) field within the [overarching] field of power […]. Second, one must analyse the internal structure of the literary (etc.) field, a universe obeying its own laws of functioning and transformation, meaning the structure of objective relations between positions occupied by individuals and groups placed in a situation of competition for legitimacy. And finally, the analysis involves the genesis of the habitus of occupants of these positions, that is, the systems of dispositions which, being the product of a social trajectory and of a position within the literary (etc.) field […]’ (Bourdieu, 2006 [1992]: 214; cf. Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 104 – 105).

Provided the lack of sufficient empirical data, the positioning of the Georgian EDMC field vis-à-vis the field of power remained at a highly suggestive level. Its general frame is informed by Bourdieu’s (2006 [1992]: 121 – 125) arrangement of the literary field within the field of power. However, I did adapt my assumed relation to the characteristics of the Georgian context by rooting it in the information provided to me by my interviewees as well as my understanding of the country from experience, observation, and research.

Similarly, the five positions occupied by my interviewees will hardly suffice to provide for an intricate field structure. To map out the structure of the field, I followed Bourdieu’s (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 230) suggestion to use a cross-tabular analysis. The rows of this table itemize the relevant agents in the Georgian field of EDMC construction whereas the columns list a spectrum of properties that differentiate those agents from one another. The comparison of the agents along the most field-pertinent properties hints toward the types of valued capitals and thus facilitates the (oppositional) positioning of the agents within the field. Provided the assumed relative similarity of the functionality of producing electronic dance music in Georgian with respective fields in other capitalist countries, I sketched out the table content using my ‘insider knowledge’ (Bennett, 2002: 460) from the scene in Berlin. Adapting this to the particularities of the Georgian context happened on the basis of my participant observations and the five qualitative interviews. Despite the lack of empirical data – and statistical imprecision –, I attempted to visualize highly conceptual maps of related positions held by agents in the field of EDMC production.

To analyze the agents’ habitus, I employed Bohnsack’s (2010, 2014) documentary method that he designed for habitus reconstruction through life-course interview interpretation. In relying on Karl Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge, the documentary method starts with the conviction that explicit verbal communication contains a layer of hidden meaning that scholars need to reconstruct in the process of interview interpretation (Bohnsack, 2014: 219). Thus, Bohnsack (2014: 225) differentiates ‘the communicative or explicit, literal and immanent meaning [from the] the conjunctive or implicit and documentary meaning.’ According to the documentary method, the latter is configured by the objective social structures that determine the interlocuter’s conduct beyond their conscious awareness and independent from their subjective meaning. The unraveling of those objective structures requires a detailed discursive reconstruction of the common ‘frame of orientation’ internalized by the various interviewees and represented in ‘collective patterns of meaning’ (Bohnsack, 2010: 104).

My study involved participants who are both male- and female-identifying, including heterosexual and non-heterosexual identifying on every gender type. Those appeared to be the most relevant types when investigating EDMC in Georgia, as the primary habitus formed in a remarkably heteronormative national context. Concretely, Gio (i1) and Beka (i4) identify as male, whereas Lana (i2), Nina (i3), and Diana (i5) identify as female. Beka and Lana indicated that they are heterosexual, whereas Gio, Nina, and Diana clarified that they are not. Beyond these differences, my interlocutors share ethnicity, nationality, age, level of education, and class affiliation, which constitute further relevant types. The social differences provided a multitude of micro-perspectives on the EDMC field in Georgia whereas the similarities presuppose a shared horizon of experience that justified the comparison of those perspectives within the context of Georgian society.

Despite the documentary method’s emphasis on the latent meaning, I also made use of the literal meaning for the formation of hypotheses surrounding the Georgian field of power and characteristics of the EDMC field, particularly for the field of EDMC consumption. The first part of the interview replicated a design formulated by Rehbein and Sommer (n.d.) that already relies on the literal meaning for life-course reconstruction. To ensure that all necessary information for life-course reconstruction is prevalent, my interlocutors filled in a survey following the interview. Moreover, since my regional-specific knowledge is limited, I complimented the interview blueprint with questions about the relationship between different societal domains , such as the government, the church, the Soviet past, along with EDMC-field-specific questions.

5. Constructing the EDMC field in Georgia

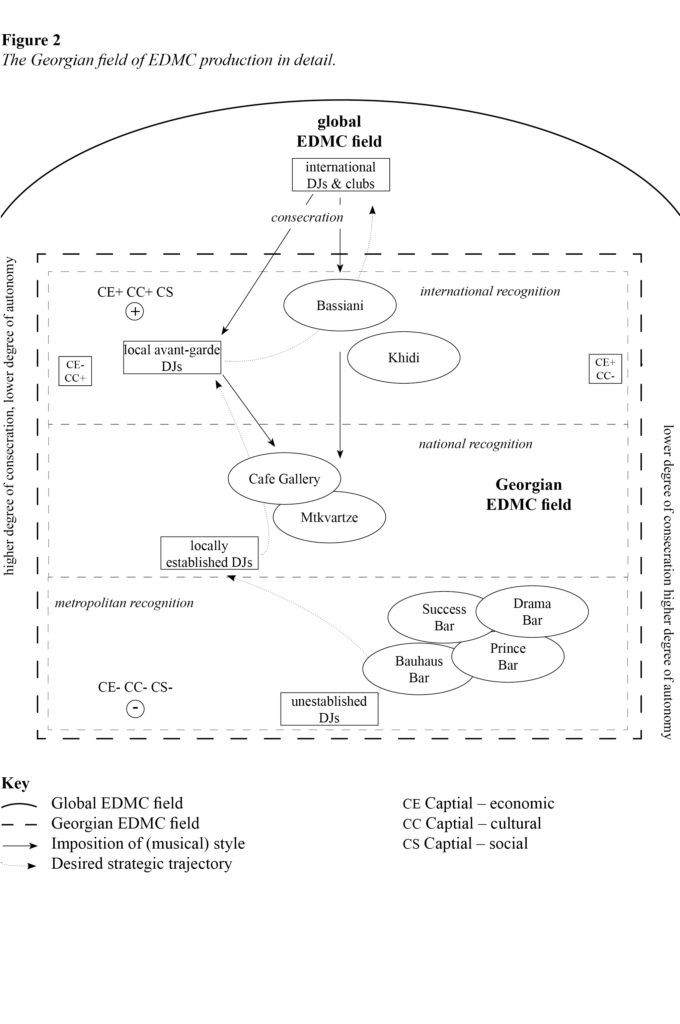

In this section, I will construct the EDMC field in Georgia. First, my analysis yielded that the Georgian EDMC field is a dominated field by the field of power, claiming high degrees of relative autonomy from it albeit not from the consecration of the global EDMC field. Second, that DJs are the main cultural producers who compete over recognition in a hierarchically structured field in which Bassiani holds institutional consecration in channeling the global influence. Third that, on the other hand, the EDMC consumers’ habitus indicates that the field of cultural consumption is driven more by alliances than by rivalry.

In present-day Georgia, symbolic power remains contested by the neoliberal government, Soviet heir, and the Georgian Orthodox Church, although my interlocutors perceived them as a unified dominant bloc operating against the dance community. Lana said that ‘politicians and priests are both preachers. When, for example, a priest has a certain type of political view, and he preaches this on to people, [and] there are like hundreds of people who think you’re holy – there are hundreds of people – and […] of course, they’re going to agree with your political opinions’ (i5: 737 – 744). According to my interlocutors, it is the church who is in power – not the state, as generally assumed by Bourdieu –, as large parts of the Georgian society are strictly religious and posit the biblical belief system over the secularized neoliberal one (i2: 256 – 257; i4: 872 – 874; i5: 741). The Christian Orthodox Church reproduces its values through institutions such as the church, schooling, the government, and the nuclear family (i4: 861 – 865; i5: 750 – 755). The reproduction of the Orthodox tradition as the dominant ideology seems to hold true for both the country’s period under Soviet developmentalism and its recent past as neoliberal democracy.

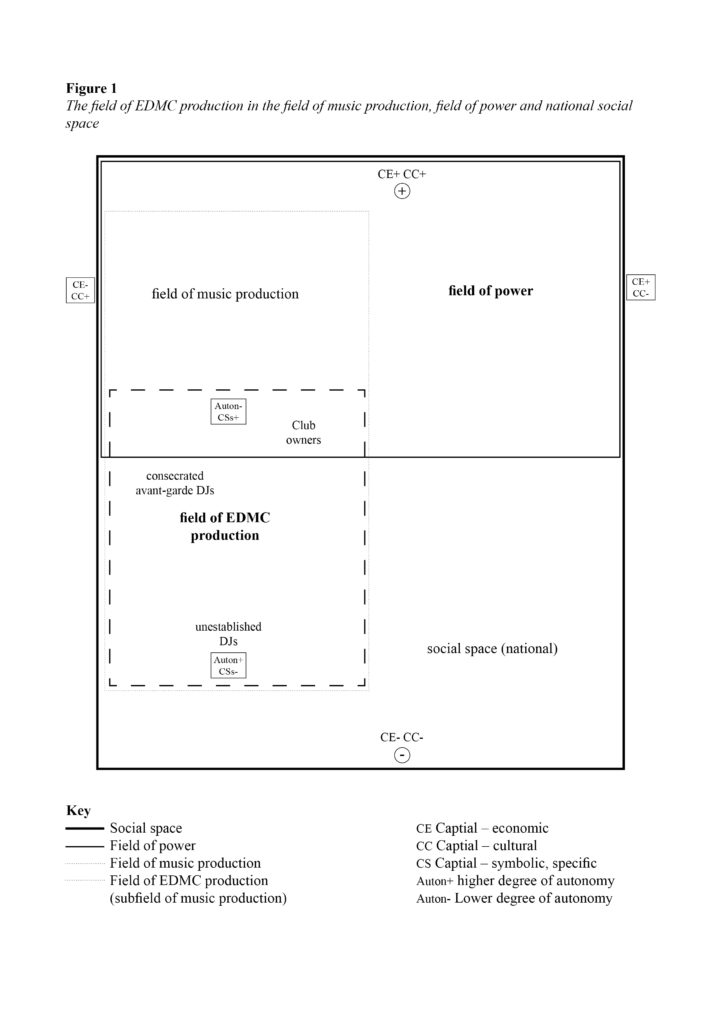

For the EDMC field this means that despite the presence of numerous venues facilitating the existence of club culture, it occupies a dominated position within the field of power, as illustrated in Figure 1. Due to the ideological discrepancies between club culture and the Georgian Orthodox Church, cultural capital accumulated by agents in the EDMC field remains unrecognized as a legitimate resource in the field of power. Diana emphasized this subordination of the club field in reporting that ‘electronic dance music is not considered a cultural activity’ (i5: 779 – 780). My other interviewees reported that the misrecognition translates to the formation of stigmas against club culture rooted in Christian chastity, the demonization of recreational substances, and heteronormativity. The stigmas are rearticulated into ‘drug dealing/addiction’ (i1: 156; i2: 236; i3: 760; i4: 617), ‘sodomy’ (i1: 390), and ‘prostitution’ (i1: 156; i2: 237). On the other hand, my interlocutors denoted Christian Orthodox tradition as ‘medieval’ (i1: 349), ‘backward’ (i1: 350), and ‘hindrance for development’ (i4: 851). This conflict plays out as a generational one: Lana said that ‘[t]his is about generations: old generations and future generations. It’s about my mom’s generation’(i2: 233 – 234), Nina confirmed that ‘conservative people are older people that were born in the Soviet Union (i3: 738), and Diana ‘would say it is […] the older generation which is more traditional and conservative (i5: 661 – 662). It follows that the EDMC field conflicts with some of the most intimate milieus of life, such as family, friends, or labor since they are predominantly structured by the Soviet past and the Christian Orthodox Church.

Although the Georgian EDMC field is struggling for recognition from the field of power, it is relatively autonomous from it compared to other fields of cultural production, such as folk music or ballet. The reason for this is that the EDMC field and the field of power are not homologous. As the audience and producers of electronic dance music tend to stem from the same age group, they often occupy a similar social position within the overall social space, i.e. a rather low overall volume of resources composed of more cultural than economic capital. Due to the nighttime setting of EDM cultural activities and the strict door policy, clubs become exclusive spaces that unapologetically deny entry to whoever appears to be an outsider, regardless of class affiliation. Therefore, there are no ‘bourgeois’ DJs linked to the dominant class, driven by economical dependency to produce according to bourgeois demand. ‘Consecration’ (Bourdieu, 2006 [1996]: 115) in the field of EDMC production is inclusively held by the local ‘avant-garde’ (Bourdieu, 2006 [1996]: 91) DJs who follow global trends of electronic dance music and adapt them to the demands of the regional crowd. Besides the local avant-garde of music production, employees of clubs and bars – such as bartenders, bookers, roadies, runners, (light show) technicians, and performers – can transform their cultural capital into economic capital beyond the nighttime. This allows them relative autonomy in the expression of an alternative lifestyle, albeit under the potential difficulties facing them in family and friendship spheres due to misrecognition from the dominant institutions. Club owners occupy the closest position to the field of power – and thus lower degrees of autonomy from it – provided their high amount of capital and relative weight of economic resources, under the necessity of complicity with regulations imposed on them from the government and market. However, for the majority of EDMC agents, the logic of the field ends with the night, as the capital accumulated in this field is incompatible with most other spheres of life, and the lifestyle requires adaptation to the spheres of labor, family, and friendship.

Internally speaking, the interviews revealed that electronic dance music culture in Georgia sprouted in 2014 with the nesting of Bassiani in the Tbilisi Dinamo Stadium and has shown enormous growth in popularity throughout the country ever since (i4: 574). Tbilisi expeditiously spawned a myriad of further nightclubs in the following years – such as ‘Khidi,’ ‘Café Gallery,’ or ‘Mtkvarze’ – and quasi-clubs – such as ‘Success Bar,’ ‘Drama Bar,’ ‘Prince Bar,’ or ‘Bauhaus Bar.’ Other Georgian cities also saw the rise of venues hosting dance events, for instance, ‘Gate’ in Batumi (i2: 176; i3: 619). Regardless, Tbilisi remains the heart of the Georgian EDMC field, spurring locals from other cities to cross the entire country for spending weekends in the capital, if they want to avoid conduct with ‘soplelebi’ (i2: 236) . Although the field geographically reaches vast stretches of the country, electronic dance music ceases to exist beyond the borders of urbanized areas, while ‘real’ electronic dance music culture is perceived to be restricted to the borders of Tbilisi.

As the geographical center of the Georgian EDMC field, Tbilisi marks the locus through which the global EDMC field exhibits its influence on the internal structure of the national field, as shown in Figure 2. I happened to run into the owner of Khidi – a Swedish migrant – on September 27, 2019, where he explained to me that he wished to construct a venue that replicates what Berlin nightlife stood for in the 90s. In accordance, the most prominent clubs in Georgia adopted some of the logics brought about by the world-famous Berliner nightclub Berghain, i.e. (a) a strict ‘face control’ (i2: 480; i3: 1069; i4: 1076; i5: 470) at the club entrance, (b) a two-dancefloor system (c) a generally dark design of the venue only interrupted by a stimulating light show (d) the presence of darkrooms, (e) an extended duration of events up to 24 hours, and (f) an international DJ line-up representing state-of-the-art musical performance. Consequently, symbolic power within the relatively autonomous Georgian EDMC field is constantly negotiated through vertical global-local relations.

With Tbilisi at the heart of the field that partially imitates global streams of EDMC, venues in Georgia’s capital hosting dance nights are structured hierarchically according to the fulfillment of standards of quality music display. The two clubs with international line-ups and linkages beyond Georgia’s borders are Bassiani and Khidi. It is noteworthy that the former tops the hierarchy and sets the standard due to its intimate connections to various well-established clubs around the world and links to advocacy groups that drive social change in favor of the field’s autonomy from the field of power. The two sites’ Friday nights are the field’s nationally acknowledged weekly main events in which local avant-garde DJs interact with internationally established DJs in the imposition of the consecrated musical styles that dominate the EDMC field. Currently, high-energetic industrial, acid, or dark techno sounds are expected on the main floor while the other commonly fuses upbeat house with disco tunes. There is not yet a remarkable distinction between commercial producers and avant-garde producers in a sense of Bourdieu (2006 [1992]: 71), as the EMDC field is not very differentiated. Local DJs are competing over bookings at the above two venues as they host the largest audience and therefore grant the most seamless conversion of cultural into economic capital, along with internationally recognized symbolic capital.

Clubs in Tbilisi that merely seize national recognition, like Café Gallery or Mtkvarze, occupy an intermediate position in the Georgian EDMC field. Their main nights occur on weekdays or Saturdays and predominantly host local DJs without international reputation. A curve of different musical styles determined by the local avant-garde and global trends fills the only available dancefloor of these spaces, typically starting with house transitioning into techno. Weekdays usually attract a smaller crowd but are also more affordable for the audience. In these spaces, nationally known DJs interact with the local avant-garde DJs, as the latter requires bookings beyond Bassiani and Khidi to maintain their lifestyle, and the former not yet receive bookings at the two prominent clubs. Therefore, national clubs are steppingstones where the not yet established producers can accumulate social capital, which my interviewees emphasized as imperative in the EDMC field (i1: 806 – 808, 880 – 881, i3: 204 – 208; i4: 177 – 179, 970 – 976). Beka said that ‘in Georgia, if you know some kind of people and if you’re a raver , like… if you are starting raving and you will meet some people, like… you won’t need to have money to for that’ (i4: 977 – 979). Given the modest size of the field, the more involved in the EDMC scene agents are, the more social capital they accumulate. Social capital is easily convertible into economic capital and necessary for cultural producers to increase their credibility.

Besides clubs with (inter)national reputation that assimilate trends in the global EDMC field, there are quasi-clubs that receive the least cultural recognition and only within Tbilisi but maintain the highest degree of artistic liberty. In Tbilisi, for example, Success Bar, Drama Bar, Prince Bar, or Bauhaus Bar fall under this category. They classify as a mixture between bar and club, meaning that is a room offering a dancefloor with DJ sets, but not necessarily following the strict club logic as described in the above participant observation. Since they do not demand an entry fee and music shifts to the background for socialization purposes sides the audience, quasi-clubs allow for more experimental musical styles often played by inexperienced DJs. These spaces provide opportunities for home producers to accumulate cultural capital in captivating the mixing skills on the (DJ-)decks and accumulate social capital that would give them entry points to performances in more renowned clubs.

Because most Georgian DJs start their career as cultural consumers and even established producers are consumers in their leisure time, the boundaries between the Georgian field of EDMC production and EDMC consumption are blurred – including the field-specific habitus. Provided Georgia’s recent transformation from communism to capitalism and the EDMC field’s struggle for legitimacy in the eyes of the field of power, it makes sense to investigate the genesis of the EDMC habitus through a double distinction: First, the generational distinction contrasting the older, pre-capitalist parent generation that embodied the dominant ‘conservative’ or ‘traditional’ habitus with the younger, post-communist generation that is in the process of acquiring a ‘progressive’ or ‘liberal’ one. Second, the distinction within the post-communist generation between the traditional primary habitus passed on to them by the parent generation followed by the later secondary habitus that sets the ground for the development into the liberal habitus.

However, since all of my interlocutors are from the post-communist generation – and more so, of the specific fragment of the post-communist generation that navigates the EDMC field –, I can only form assumptive statements about the traditional habitus. They reported that family members, as well as former friends, do not ‘understand’ their affiliation with club culture (i1: 263 – 264, 296 – 302; i2: 233 – 239; i3: 716 – 718, 877 – 881; i4: 726 – 730; i5: 599 – 600), hinting toward sets of dispositions that produce diverging schemes of perceptions and appreciations. The exact characteristics of this traditional habitus remain unclear. The result of a deduction from my study participants’ shared primary habitus merely revealed that it is conform to traditional gender roles (i3: 691; i4: 731 – 733, 791 – 792; i5: 69 – 62) and imprinted with Orthodox Christian belief (i2: 257 – 264; i3: 42 – 46, 53 – 59; i4: 798 – 802, 877 – 880) and Soviet values (i1: 482 – 483; i2: 373 – 378; i3: 17 – 20; i4: 531 – 534; i5: 635 – 637).

Therefore, my analysis focuses on the secondary, liberal habitus that intends to deconstruct the primary, traditional one. My interviewees emphasized that exposure to electronic dance music culture was a monumental turning point in their life (i1: 579; i2: 410; i3: 682 – 685; i4: 673). ‘I think it’s forever,’ Gio (i1: 176 – 178) said, ‘I was like… my whole life changed. I can’t remember my part of him who I was before these raves.’ With similar conviction, Lana (i2: 404 – 410) claimed that it is ‘because it changed your mind, it changed your lifestyle, and it changed everything that was in your life before.’ It follows that my interviewees perceive a categorical difference in their primary habitus and their developing secondary habitus.

The interview interpretation revealed that some of the relevant habitus traits pertinent to the EDMC field are self-confidence (i4: 293 – 295, 454 – 458; i5: 287 – 289), autonomy/independence (i1: 907 – 908; i2: 224 – 226; i3: 569 – 572), determination (i1: 917 – 918; i3: 327 – 328; i4: 150 – 152, 314), communication (i2: 23 – 26; i4: 116 – 119), and cosmopolitanism (i3: 117 – 120; i4: 291 – 294; i5: 109). Most of these traits can be traced back to my interviewees’ sole exposure to Georgia as integrated into globalized neoliberal capitalism or oppression from the nationally dominant cultural order. Specifically, but not exclusively, the non-heterosexual type of my interlocutors stressed that agents adapting an EDMC lifestyle require self-confidence and independence to uphold their identity against the friction of everyday judgment and discrimination. Determination is the necessary condition in an allegedly merit-based labor market. As a country where social capital plays a paramount role in virtually every facet of life, interpersonal communication skills become leverage for opportunity and experience. Particularly digital media and the international flow of people account for the relevance of cosmopolitanism in the constitution of the EDMC habitus. More tangibly, my interviewees testified that they can recognize another raver immediately by their way of talking, their way of moving, or their style, albeit latest after a short conversation that would reveal (in)congruent ‘vibes’ (i4: 422). Against my assumption that EDMC agents embody a heterogenous habitus, most of my study participants said that they do not negotiate their lifestyle with clashing milieus of life while actively intending to replace their primary habitus with the liberal one.

Linking this habitus back to the EMDC field, my analysis yielded that the dynamics are indeed less determined by an internal competition than by coalescence to oppose external political subjugation. The conduct between EDMC agents was described by my interviewees to be genuine and solidary, facilitating community building, the empowerment of an alternative lifestyle as well as commitment to collective action. Agents assert each other’s identity by giving compliments and thus boosting confidence (i5: 391 – 396). A culture of mutual caretaking harnesses the ones fallen for the exuberance of recreational substances (i2: 460 – 462; i4: 688 – 694). Emotions bounce back and force between agents on the dancefloor and are shared in social networks thereafter (i1: 576 – 579; i2: 458 – 462). Social networks moreover enable calls for financial support in case of skyrocketing fees imposed on individuals who were busted by cops with liminal amounts of drugs (i1: 612; i2: 462 – 463). ‘We stay strong, and it makes us stronger and stronger against the system,’ Gio (i1: 612 – 624) manifested, ‘and the Bassiani sign [stands for] “we fight together.” […] We dance together, and we need to fight together – we are fighting against it!’

6. Conclusion: More than musical ecstasy & more research to be done

In this paper, I studied Georgian electronic dance music culture under a research paradigm informed by Bourdieu’s sociology. First, I lay out the theoretical foundation of Bourdieu’s field theory, in which he relates his concepts of capital, habitus, and field to analyze the social cosmos under investigation. Subsequently, participant observations in the country harbored my research assumptions, viz. that the container nation-state is insufficient for the Georgian EDMC field construction, that it is less determined by internal competition than generally assumed by Bourdieu, and that agents navigating the field simultaneously embody a plurality of habitus. To confront these hypotheses, I conducted five qualitative life-course interviews with members of the Georgian post-communist generation who identify as members of the dance community and interpreted them using Bohnsack’s documentary method.

The study results indicated that the Georgian EDMC field occupies a dominated position within the field of power. As a field of cultural production, agents navigating the Georgian EDMC are driven by the necessity to convert their field-specific capital into economic capital. Although symbolic power remains contested between the Georgian Orthodox Church, neoliberal government, and heir of Soviet developmentalism, my analysis yielded that they share a commonality of not recognizing the authenticity of the EDMC field including the lifestyle it produces. However, the Georgian field of EDMC remains relatively autonomous from the field of power, since cultural production is preserved for an audience that tends to exclude agents posited in the field of power while global electronic musical trends designate consecration. Via the accumulation of specific cultural and social capital, local DJs compete over (inter)national recognition that grants them access to the most prestigious nightclubs allowing for the most seamless conversion of their resources into economic capital. Lastly, the analysis of my interlocutors’ habitus revealed that externally imposed political oppression dismantles internal competition in the field of EDMC consumption. Post-communist EDMC agents form alliances to empower an alternative lifestyle that resists social subjugation by actively deconstructing the traditional habitus embodied from the pre-capitalist parent generation. Therefore, they levitate affiliation to club culture beyond individual longing for drug-induced dissolution into hedonistic musical ecstasy.

Nonetheless, the study brought up more questions than it gave answers. Future research about EDMC in Georgia will primarily need to deeper investigate the struggle for symbolic power happening against the country’s history as a post-Soviet nation transitioning to neoliberal capitalism, as this marks the main difference between Georgia and conventionally analyzed countries by Bourdieu. It remains unclear how Christian Orthodox tradition, neoliberal principles, and aftermath of Soviet ideology negotiate their conflicting values in the struggle for symbolic capital. Moreover, it is necessary to elaborate on how the country’s transition into neoliberal capitalism spawned and solidified social classes that catalyze social inequalities. Although I distinguished habitus formation rooted in generational difference, I assume that is more class-based than demonstrated in my study, as my interlocutors are in the same class inherited by their parents. Amongst others, this requires the qualitative investigation of what I described here as the pre-capitalist generation to concretely discern their conservative habitus juxtaposing the post-communist generation’s liberal one. Moreover, it is necessary to more meticulously fracture the category ‘youth,’ as the group is less internally homogenous as assumed here. There must be at least one opposing juvenile social group that adopts the dominant values and beliefs from which EDMC agents distinguish themselves. Generally, larger empirical samples of the social strata under investigation would grant higher degrees of representativeness than this study can claim. Accordingly, my analysis of the field of Georgian EDMC production including its relative position vis-à-vis the field of power remains highly conceptual and requires testing with empirical data. The study assumed that global-local positions are mobilized reflexively by EDMC agents alongside other markers of social difference and coherence. However, more work is needed to identify the way agents strategically take positions amid an increasingly complex interplay of local and global influences. A critical factor that Bourdieu disregarded entirely due to its nonexistence at the time of his publication is the rise of social media and the impact it has on local dynamics. Further research into the potential of the Georgian EDMC as a driver of social change is needed to discern whether the resistance culminates in higher degrees of acceptance. And ultimately, more work is needed to discern how club culture reproduces some of the social inequalities that it seeks to overcome.

References

Bennett, A. (2002). Researching Youth Culture and Popular Music: A Methodological Critique. British Journal of Sociology, 53(3), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007131022000000590

Bohnsack, R. (2010). Documentary Method and Group Discussions. In R. Bohnsack, N. Pfaff, & W. Weller (Eds.), Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method: In International Educational Research (pp. 99–124). Verlag Barbara Budrich. https://doi.org/10.3224/86649236

Bohnsack, R. (2014). Documentary Method. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. SAGE.

Bourdieu, P. (1987). What Makes a Social Class? On The Theoretical and Practical Existence Of Groups. Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 32, 1–17. JSTOR.

Bourdieu, P. (1989). Social Space and Symbolic Power. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.2307/202060

Bourdieu, P. (2000). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (Reprint1984 ed.). Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2006). The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field (Nachdr). Stanford Univ. Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2008). The Logic of Practice (Reprinted). Stanford Univ. Press.

Bourdieu, P., Darbel, A., & Schnapper, D. (1991). The Love of Art: European Art Museums and their Public. Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Polity Press.

Giddens, A. (2003). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Reprint). Polity Press.

Mebagishvili, T., Gavashelishvili, E., Ladaria, K., Khinchagashvili, S., & Ratiani, S. (2012). The Orthodox Church and the Reframing of Georgian National Identity: A New Hegemony? [Paper for the ECPR General Conference].

Nikolayenko, O. (2007). The Revolt of the Post-Soviet Generation: Youth Movements in Serbia, Georgia, and Ukraine. Comparative Politics, 39(2), 169–188. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/20434032

Rehbein, B., & Sommer, I. (n.d.). Critical methodology: Research on inequality as a learning process. Unpublished Manuscript.

Roberts, K., Pollock, G., Tholen, J., & Tarkhnishvili, L. (2009). Youth leisure careers during post‐communist transitions in the South Caucasus. Leisure Studies, 28(3), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360902951666